We Are Here with Leiko Ikemura

Introduction

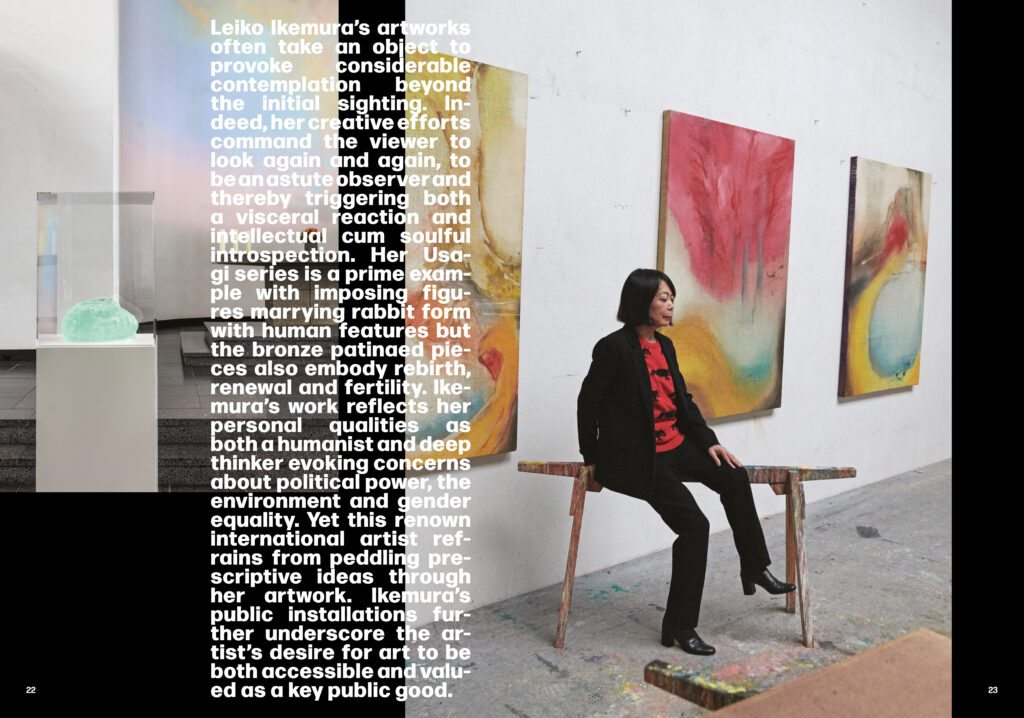

Leiko Ikemura’s artworks often take an object to provoke considerable contemplation beyond the initial sighting. Indeed, her creative efforts command the viewer to look again and again, to be an astute observer and thereby triggering both a visceral reaction and intellectual cum soulful introspection. Her Usagi series is a prime example with imposing figures marrying rabbit form with human features but the bronze patinaed pieces also embody rebirth, renewal and fertility. Ikemura’s work reflect her qualities as both a humanist and deep thinker evoking concerns about political power, the environment and gender equality. Yet this renown international artist refrains from peddling prescriptive ideas through her impressive body of work. The numerous installations of Ikemura’s works in public spaces further underscore the artist’s desire for art to be both accessible and valued as a key public good.

JL: You have lived a very peripatetic existence – born in Japan, studying in Spain before living in Switzerland and Germany. Could you briefly describe your initial experiences in Europe and indicate how this impacted on your art?

IL: Attending art school in Seville was something completely different to what I had experienced in Japan. It was a special situation in that I was the only foreigner. Beyond that, my foray into Spain transpired during the Franco time when things were utterly different. My academic study in Spain was useful, as it allowed me a unique development. I began studying the Spanish language and later advancing my interest in art through the encounter with the Spanish art scene at that time. Remember, Spain in the 70ies had very little contact with the rest of the world. On completion of my studies, I went to Switzerland at the beginning of the 1980ies, where I began to explore life as an artist. At that time, there was a considerable political and critical impact from the youth in Switzerland that offered me a vivid view of the life in Zurich. Also, Transavanguardia in art was embraced by artists in countries such as Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, Holland and indeed the rest of the world. The art scene was then dominated by men, which made me an exceptional figure as a young female artist. Initially, it was a struggle to carve out an existence given the absence of scholarships/bursaries. Therefore, it took years for people to start noticing my work. However, I started to find my own artistic language in Switzerland due to the country’s open art system and the then rise of Transavanguardia.

JL: In several interviews, you generously use the word “freedom.” Why is freedom such an important force in both your life and artistic work.

IL: The personal and artistic pursuit of freedom remains essential. Searching for freedom in every sense is an important endeavour, but, in a way, that does not belong to any special group or movement. Of course, the craving for freedom is always challenging, as it often leaves one without protection. Fighting for freedom remains a life attitude for me as a human being, as a woman, and as an artist with responsibility. This achievement means a paramount commitment along with a deep awareness of political, gender and climate issues. As an artist, I seek to deploy a holistic sensitivity to the multiple challenges we face as mankind.

JL: You show immense political, gender, social and political sensitivity and yet your works seek not to prescribe but instead invite us to reflect.

IL: Many thanks for such a beautiful observation. I approach making art in that manner, as my interest is not to manipulate people’s thoughts. Instead, I am far more interested in fashioning a sensibility that itself is a form of openness. Therefore, viewers of my art are also free to interpret. Yes, there are also numerous signals, which I readily concede are not clear to me! Therefore, I would not say that my use of a certain figurative moment conveys a very specific message. My works seek to transmit a host of messages, but not in a conventional or politically correct manner because every form with a powerful message could be accompanied by aspects that are not necessarily really honest. Also, you know, I really want to remain close to the truth, which cannot be reduced to a singular word or ascribed. Artistic truth remains both a form of honesty and a kind of sensibility.

JL: You appear to be pushing the boundaries of your artistic endeavour as evinced from your use of multiple media – paintings, glass, ceramics and of course the fantastical bronze sculptures. What explains the use of these different media, and do they shape your artistic expression?

IL: Yes, for sure! I think my interest in various art media stems from the times we live in. That is, things are no longer dominated by the 20th-century notion of an artist being a specialist and working with a single medium. I was always missing the spirit of Da Vinci who of course mastered many disciplines. I also believe we need to have a broader overview of numerous materials and techniques, as it engenders the flexibility to break the borders between nationalities, gender and media. Added to that, my deep artistic curiosity pushes me to go farther and offers me another challenge. For example, creating a glass sculpture fuelled both my fascination and inspiration. The created artworks also allow the emergence of connections among them with each other. I can use the same form, but the difference in either material or the quality of the material allows a surprising perception, especially in the way light comes through a glass sculpture.

JL: Another fascinating aspect of your work are the landscapes that tend to project an allegorical quality. For example, your piece called Berlin Horizon is bent to not reflect things as they are but rather evokes either a dream or a statement of how you would like things to be.

IL: Perhaps the landscape paintings aspire to be both. But generally speaking, they are meant to be allegorical and yet in a non-descriptive way. Yes, these works project numerous non-realistic stories that are not descriptive. Instead, they are visual stories aimed at reflecting dreams of a world that remains invisible. So, I think it is through presenting this world that we can visualize another reality. Yes, I remain most curious about this invisible world, even if you feel this world is in the shadow. I see the reflection, and, suddenly, I start imagining the importance of this immaterial world. Of course, material things enrich our lives, but we tend to become far too obsessed with them. We also need the metaphysical, even more now with the declining importance of religion in our lives. So, the metaphysical becomes our collective need and my own need. I think it is a human endeavour to have spiritual power and to learn its use and application.

JL: Your reference to spirituality triggers a question about your work in Saint Matthew’s church in Berlin. Here, the art appears to reflect a concern about the COVID-19 triggered lockdown and its impact on daily life. You appear to be inviting reflection on the expression of freedom. But what was the general reaction to your work in Saint Matthew’s Church?

IL: The viewing public’s reaction was the most touching, as it was also a form of protest to the closure of galleries and museums. Of course, the protective measures are necessary, but we also need to continue to live and pursue daily lives. Bear in mind, museums and galleries pose limited public health risks, as they tend to be both spacious and well ventilated. The opportunity to work on the exhibition at St. Matthew’s church was both an interesting opportunity and a coincidence. It emerged during the planning process that churches might be the only locations where artists could exhibit their work. I grabbed the chance, as it was interesting to be artistically active while remaining conscious of the prospect to react to the pandemic-induced situation. Realizing the exhibition was not an easy task, but I also learnt to make the very best of a challenging situation. The exhibition at St. Matthew’s also served as a reminder of the interesting tradition of churches with their free spirit and independence from other systems. Bear in mind that St. Matthew’s previously housed a Gilbert and George exhibition.

JL: That exhibition at St. Matthew’s Church also resulted in the publication of the book – In Praise of Light. Could you explain the motivation behind this book?

IL: The book’s title reflects a play on the title of the book In Praise of Shadow by Jun’ichoro Tanizaki. For example, he criticizes modern architecture, which is generally preoccupied with light – hence conjuring buildings with large windows that convey brightness. As humans, we endeavour to avoid darkness and search for light instead. But he commends the beauty of shadow, praising it’s presence as an ambiguous in between space. On the other hand, I feel compelled to say something about the enduring power of light as a metaphysical quality. The catalogue features conversations among art historians and a priest. An experimental performance was presented with a dancer, another artist and a musician – three women accompanied me during the performance. The church has huge glass windows, which I modified with a translucent cover. This allowed one to be in a space of apparent refuge while benefitting from the warm translucent light. My paintings for the windows were relatively small and yet strong enough to match the cavernous space.

JL: Your works are being exhibited in a host of important venues. The current one in Valencia carries the playful and ambiguous title “Here We Are”. What lies behind the title?

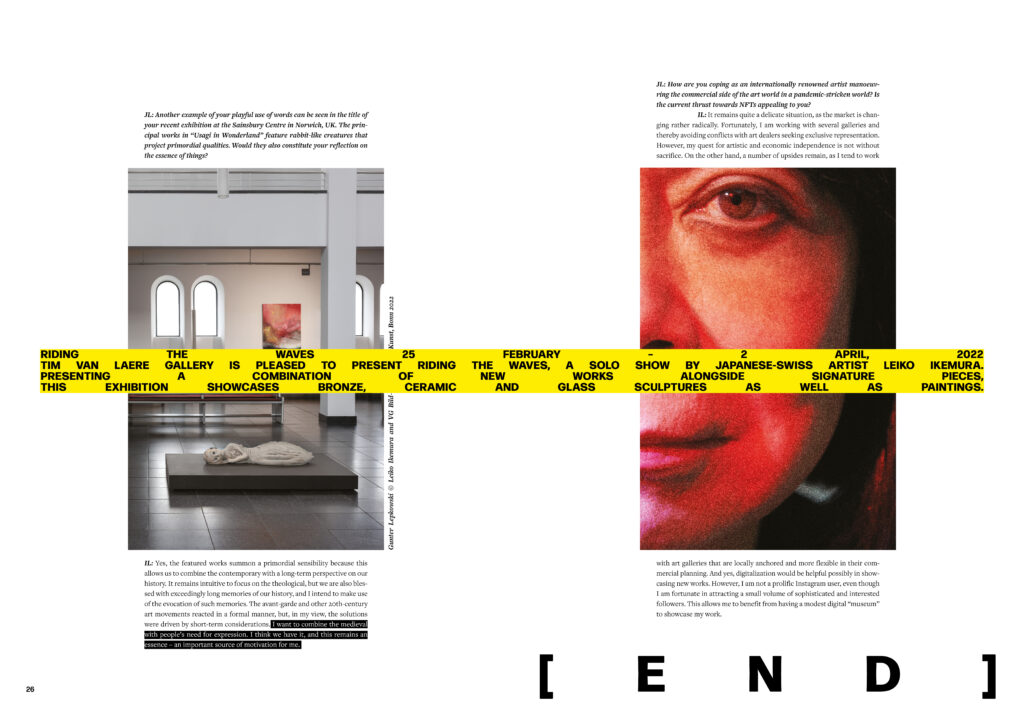

IL: Yes, the title partially reflects a sense of humour. But it also reflects a recognition of the current situation responding to global developments or the current human condition. The Valencia installation with a huge standing sculpture and five reclining figures are installed on the pond in front of the monumental architecture, designed by Santiago Calatrava. “Aqui estamos” in Spanish is a statement of our power and poetry indicating Now and Here as a huge possibility. My upcoming exhibition at Tim Van Laere Gallery in Antwerp, Belgium is titled “Riding the Waves”. I feel we need another kind of energy, and we should therefore restart and reset everything. Hence, I wanted to make an installation featuring a sizeable, wave-like ensemble of sculptures evoking an architectural intervention. Waves are also very much an elemental form with a kind of self-replicating roundness that is complete. Waves also represent a form of movement that I somehow feel I understand. Titling an exhibition is always a declaration of intent, a polemical statement.

JL: Another example of your playful use of words can be seen in the title of your recent exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, UK. The principal works in “Usagi in Wonderland” feature rabbit-like creatures that project primordial qualities. Would they also constitute your reflection on the essence of things?

IL: Yes, the featured works summon a primordial sensibility because this allows us to combine the contemporary with a long-term perspective on our history. It remains intuitive to focus on the theological, but we are also blessed with exceedingly long memories of our history, and I intend to make use of the evocation of such memories. The avant-garde and other 20th-century art movements reacted in a formal manner, but, in my view, the solutions were driven by short-term considerations. I want to combine the medieval with people’s need for expression. I think we have it, and this remains an essence – an important source of motivation for me.

JL: How are you coping as an internationally renowned artist manoeuvring the commercial side of the art world in a pandemic-stricken world? Is the current thrust towards NFTs appealing to you?

IL: It remains quite a delicate situation, as the market is changing rather radically. Fortunately, I am working with several galleries and thereby avoiding conflicts with art dealers seeking exclusive representation. However, my quest for artistic and economic independence is not without sacrifice. On the other hand, a number of upsides remain, as I tend to work with art galleries that are locally anchored and more flexible in their commercial planning. And yes, digitalization would be helpful possibly in showcasing new works. However, I am not a prolific Instagram user, even though I am fortunate in attracting a small volume of sophisticated and interested followers. This allows me to benefit from having a modest digital “museum” to showcase my work.