RE/STORE : Belgium, Congo and in Between

Conversation with Jean Pierre Müller on the AfricaMuseum Renovation, Belgian Colonisation and the RE/STORE Project

This brief tale begins with a missed opportunity. Jean Pierre Müller and I are heading in the back of a cavernous Uber van to the Royal Museum of Central Africa (now rebranded as the AfricaMuseum). We are engrossed in conversation about the RE/STORE project – an artistic collaboration between Müller – a Belgian painter – and Aimé Mpane – a Congolese sculptor. On reflection, Müller and I recognised that it might have been instructive to invite the dreadlocked Uber driver into our chat. Had he visited the institution, had he seen the renovated space, had he read reviews of the new permanent exhibition? So many questions should have directed at Gerrard, more so given that he reflects one of the museum’s target groups by apparently being of African heritage and domiciled in Belgium.

Before entering the renovated rotunda at the museum, we see an impressive 22m dugout canoe – remarkably a gift from a Congolese regional administration. Sight of the vessel summons images of Africans crossing the Mediterranean Sea in boats to enter Europe. But the boat being lodged in the long passageway linking the newly constructed wing with the longstanding building also suggests moving the perspectives of the principal actors – Belgium and Central Africa. The white wall of the long passageway is adorned with a sagacious text in multiple languages – “everything passes but the past!” We cannot change history, but can we shed new light on it?

The AfricaMuseum was first commissioned by Leopold II to attract investors to support his colonial project in Congo. Accordingly, the institution’s original name was Museum of the Congo. What emerged re both architecture and exhibited material was a homage to Leopold II’s colonial exploits. This can be readily evinced from the Grand Rotunda where the dome is decorated with the king’s double L logo, while the star of the Congo Free State (surely a case of malapropism) is etched on the fine marble floor. Indeed, the entire ethos of the museum was an unfettered glorification of Belgian colonisation of Congo. That is, until the renovation began in 2013 to not only update the physical infrastructure but more importantly detoxify the omnipresent colonial fervour embedded in the displayed artworks. The revamp notwithstanding, the modernised space remains replete with artworks inscribed with the key colonial message – Belgium Brings Civilisation to Congo!

Retiring the museum’s role in propagating a benevolent role Leopold II as well as Belgium as colonial powers, stereotypically racists artworks are now displayed in a small room. Müller explains that the dominant propaganda resulted in the demonization of native Congolese – dismissed as being bereft of any civilization before the arrival of Belgium in their country. Hence, RE/STORE’s primary artistic endeavour was to document, depict and restore the strengths of Congolese civilizations through new interpretations of artworks.

We reach the main building and view a panel inscribed with the names of 1508 Belgians that died in Congo during the period 1868 – 1908. A quote from Albert I – Leopold II’s successor, adorns the panel and serves to reinforce the message of Belgian benevolence towards Congo: “Death reaped mercilessly among the ranks of the first pioneers. We can never pay sufficient homage to their memory.” The sole reference to Müller prompted a brief meditation on acts the artist’s forefathers might have committed during Leopold’s II foray in Congo. How do Belgians with mixed African and European ancestry process and meander this challenging period of Belgian history? The reflection became more personal – does my new Belgian citizenship require full ownership of my adopted country’s history?

The museum’s Grand Rotunda remains replete with 16 gold gilded statues representing various facets of Belgian benevolent colonisation. The names of the statues are illuminating – Belgium Brings Well-Being Civilisation to the Congo; Belgium Brings Well-Being to the Congo; Belgium Brings Security to the Congo; Charity; Dry Season; Fertile Africa; Justice; Man at his Toilet; Negress with Amphora; The Paddler; Slavery; The Tamtam Dancer; The Warrior; and The Worker all being highlights. The original artworks’ message remains unambiguous – Belgians are bringing civilisation to Congo that lacked any such prior history. As Adam Hochschild noted in The Atlantic “Africans are represented as smaller than Europeans or reduced to the activities they practice [while] African women are sexualized.”

Several of the original statues depict rape, lust and evil, with naked African bodies galore. There are strong expressions of the dominant fetishization of Africans, with a stark sexualised gaze reserved for African women. In one figure, a great worker with a well-conditioned body is celebrated for his work but remains represented primitive. Another male figure lacks a sexual organ and is therefore neutered. This secular European fascination with the black body is paired with serial sexual repression. Europeans gazed at, feared, fetishized and fantasised the black body while depicting the African male as corporally powerful but bereft of a brain.

Tasked with changing the rotunda’s narrative, Mpane crafted two huge wooden pieces – New Breath, or Burgeoning Congo and Lusinga’s Skull. The former depicts an African male head to celebrate the continent’s promising future, with references to Congo’s prosperity from both its people and natural wealth. In contrast, Lusinga’s Skull showcases the killing and beheading of a Congolese chief by Belgian forces in December 1884 and therefore connotes the destruction – human and physical – that marked Congo’s colonial past. The imagery of Lusinga’s exposed skull reflects Congoleses’ enduring dignity in the face of Belgian colonisers’ rampant violence.

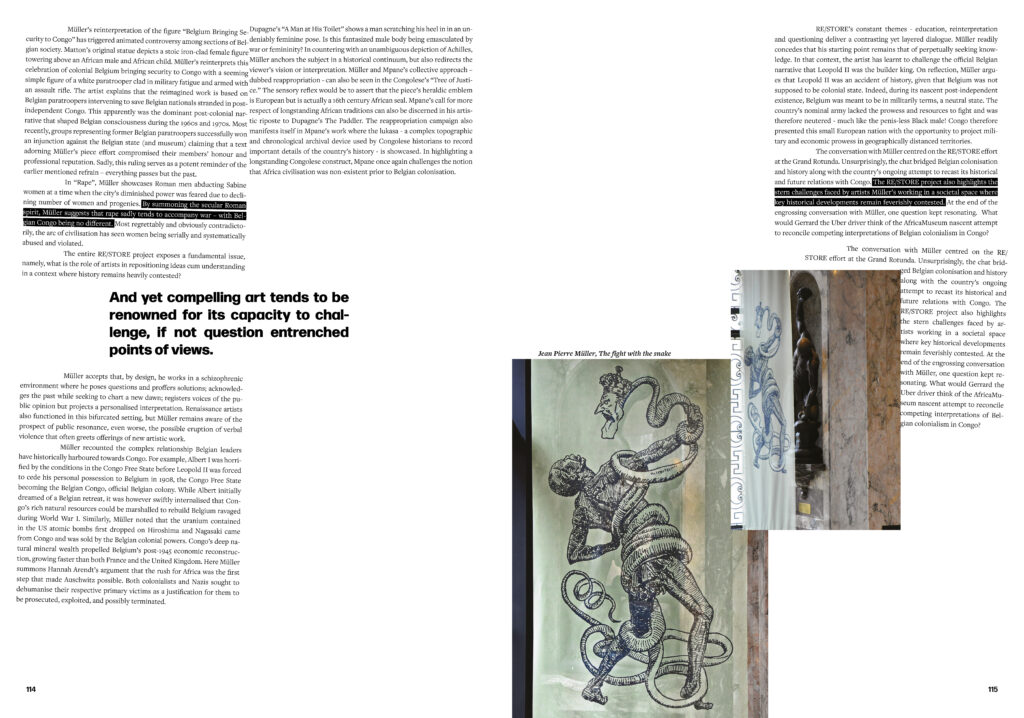

Mpane’s two sculptures contrived dialogue between a violent past and prosperous future physically dominates the rotunda. To further decolonise the rotunda’s toxic propaganda pitch, Mpane was commissioned to offer new reinterpretation to the 16 existing colonial figures. For this purpose, he offered to share the reflection, the burden and the heritage with a Belgian artist and friend – Müller. Enter RE/STORE – a creative project resulting in superimposing fabric-based veils on the existing statues to offer a new interpretation. The artists’ brief was not to erase the past but to reposition the narrative through the creation of an additional layer that questions, elucidates and reimagines.

Beyond the artists’ disposition to apply a different language, the painted plaster of the original artworks coupled with their classified nature shaped the new creations. There is a symmetry between Mpane and Müller – both occupy the same age cohort, and both exercise the same creative professions as their respective fathers. The two artists felt uncomfortable with the thought of destroying objects of the past. Instead, they quickly settled on adding additional layers to a permanent installation. It is ironic that the RE/STORE project has resulted in the enhanced physical illumination of the rotunda’s original artworks! This enlightened form of showcasing allows not only enhanced visibility but also spurs an instant dialogue between the past and current artistic narratives. The 16 new creative unions generate interplays but also chart a new “third” artwork – best seen in Mpane’s “Charity” where sunlight beams unto the laminated plastic and then reflects unto the textile.

Mpane and Müller both apply their respective deep knowledge of European art history to craft RE/STORE pieces. Most notably, Müller’s Joueuse de Lyre supplants the oversexualised black female nude in Dupagne’s Tamtam Dancer with a painting of Cléo de Mérode (reportedly one of Leopold II’s numerous lovers) as a clothed Greek goddess playing the lyre. But the two artists also generously use wit to counter the narrative of Belgians as benevolent colonisers. Mpane recasts the original The Warrior (the piece with the absent penis) with an inverted wheelbarrow of dripping bananas with the refrain “throw it away.” By reappropriating an ultra-racist theme sadly pervasive in many European societies, the Congolese artist summons us to finally retire (throw away) these racist tropes. In similar vein, Müller reimagines Wynants’ Fertile Africa as Rubber Man, borrowing imagery of the Michelin Man. The use of wit should never diminish the earnestness with which both Mpane and Müller seek to challenge the colonialism embedded in the original works in the museum’s rotunda.

Müller’s reinterpretation of the figure “Belgium Bringing Security to Congo” has triggered animated controversy among sections of Belgian society. Matton’s original statue depicts a stoic iron-clad female figure towering above an African male and African child. Müller’s reinterprets this celebration of colonial Belgium bringing security to Congo with a seeming simple figure of a white paratrooper clad in military fatigue and armed with an assault rifle. The artist explains that the reimagined work is based on Belgian paratroopers intervening to saving Belgian nationals stranded in post-independent Congo. This apparently was the dominant post-colonial narrative that shaped Belgian consciousness during the 1960s and 1970s. Most recently, groups representing former Belgian paratroopers successfully won an injunction against the Belgian state (and museum) claiming that a text adorning Müller’s piece effort compromised their members’ honour and professional reputation. Sadly, this ruling serves as a potent reminder of the earlier mentioned refrain – everything passes but the past.

In “Rape”, Müller showcases Roman men abducting Sabine women at a time when the city’s diminished power was feared due to declining number of women and progenies. By summoning the secular Roman spirit, Müller suggests that rape sadly tends to accompany war – with Belgian Congo being no different. Most regrettably and obviously contradictorily, the arc of civilisation has seen women being serially and systematically abused and violated.

The entire RE/STORE project exposes a fundamental issue, namely, what is the role of artists in repositioning ideas cum understanding in a context where history remains heavily contested? And yet compelling art tends to be renowned for its capacity to challenge, if not question entrenched points of views. Müller accepts that, by design, he works in a schizophrenic environment where he poses questions and proffers solutions; acknowledges the past while seeking to chart a new dawn; registers voices of the public opinion but projects an individualised interpretation. Renaissance artists also functioned in this bifurcated setting, but Müller remains aware of the prospect of public resonance, even worse the possible eruption of verbal violence that can greet offerings of new artistic work.

Müller recounted the complex relationship Belgian leaders have historically harboured towards Congo. For example, Albert I was horrified by the conditions in the Congo Free State before Leopold II was forced to give up his personal possession to Belgium in 1908, the Congo Free State becoming the Belgian Congo, official Belgian colony. While Albert initially dreamed of a Belgian retreat, it was however swiftly internalised that Congo’s rich natural resources could be marshalled to rebuild Belgium ravaged during World War I. Similarly, Müller noted that the uranium contained in the US atomic bombs first dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came from Congo and was sold by the Belgian colonial powers. Congo’s deep natural mineral wealth propelled Belgium’s post-1945 economic reconstruction – growing faster than both France and the United Kingdom. Here Müller reminds me of an argument made by Hannah Arendt identifying the rush for Africa as the first step that made Auschwitz possible. Both colonialists and Nazis sought to dehumanise their respective primary victims as a justification for them to be prosecuted, exploited, and possibly terminated.

Dupagne’s “A Man at His Toilet” shows a man scratching his heel in in an undeniably feminine pose. Is this fantasized male body being emasculated by war or femininity? In countering with an unambiguous depiction of Achilles, Müller anchors the subject in a historical continuum, but also redirects the viewer’s vision or interpretation. Müller and Mpane’s collective approach – dubbed reappropriation – can also be seen in the Congolese’s “Tree of Justice.” The sensory reflex would be to assert that the piece’s heraldic emblem is European – it is actually a 16th century African seal. Mpane’s call for more respect of longstanding African traditions can also be discerned in his artistic riposte to Dupagne’s The Paddler. The reappropriation campaign also manifests itself in Mpane’s work where the lukasa – a complex topographic and chronological archival device used by Congolese historians to record important details of the country’s history – is showcased. In highlighting a longstanding Congolese construct, Mpane once again challenges the notion that Africa civilisation was non-existent prior to Belgian colonisation.

RE/STORE’s constant themes – education, reinterpretation and questioning deliver a contrasting yet layered dialogue. Müller readily concedes that his starting point remains that of perpetually seeking knowledge. In that context, the artist has learnt to challenge the official Belgian narrative that Leopold II was the builder king. On reflection, Müller argues that Leopold II was an accident of history, given that Belgium was not supposed to be colonial state. Indeed, during its nascent post-independent existence, Belgium was meant to be in militarily terms, a neutral state. The country’s nominal army lacked the prowess and resources to fight and was therefore neutered – much like the penis-less Black male! Congo therefore presented this small European nation with the opportunity to project military and economic prowess in geographically distanced territories.

The conversation with Müller centred on the RE/STORE effort at the Grand Rotunda. Unsurprisingly, the chat bridged Belgian colonisation and history along with the country’s ongoing attempt to recast its historical and future relations with Congo. The RE/STORE project also highlights the stern challenges faced by artists Müller’s working in a societal space where key historical developments remain feverishly contested. At the end of the engrossing conversation with Müller, one question kept resonating. What would Gerrard the Uber driver think of the AfricaMuseum nascent attempt to reconcile competing interpretations of Belgian colonialism in Congo?

Words: Junior Lodge

Photos: Jean Pierre Müller